From 1980 to 2015, in what was undoubtedly one of the single greatest moments in human history, China reduced its official poverty rate by 95 percent. The following are notes from some prominent literature that discuss how this happened and the significance (or lack thereof) of decentralization in that journey.

In economic theory, those in favor of decentralization argue that actual decentralization allows competition and allows local actors to benefit from the products of their own work, creating incentives and personal stakes to work in public interest (see Cooter, 2003; Kotsogiannis and Schwager, 2006; Shah, 1997; Shleifer and Vishny, 1993). Such economists also identify the positive externalities of information spillovers from regional experimentation which can be richly pedagogical for both the center and other states. Moreover, they argue, decentralization weakens corruption because competition among subnational governments constrains bureaucratic behavior.

Those in opposition to decentralization argue for central planning given the large amount of information that they believe is required for planning. They highlight the distributional effects—decentralization could amplify regional inequality. Local leaders are also likely to be risk averse vis a vis the centre on experimentation due to a lack of political hedging for the former—local leaders have all their eggs in just that one basket (see Cai and Treisman, 2008; Weingast, 2008).

Jin, Qian, and Weingast (1999) and Weingast (2008) stress on adopting their “second generation theory” of decentralization and their ideal model of it. They establish two prerequisites for decentralization to become actual: first, interregional competition or, in other words, the lack of regional protectionism, and second, the retention of marginal revenues—linking local budgets with local revenues. Essentially, anything your jurisdiction makes over $x is yours. This, they posit, is meaningfully distinct from the first generation model of fiscal federalism. In the first generation, Hayek (1945) emphasized the advantages of decentralized decision-making in terms of best utilizing local information. Whereas, Tiebout (1956) argued that competition among local governments on expenditure allocation allows residents to sort themselves and match their preferences with a particular menu of local public goods—a sort of spatial equilibrium model where the preferred state of the world is for residents to move to better off regions rather than to fight regional inequality. Musgrave (1959) and Oates (1972) believed that decentralized allocations were the appropriate assignment of taxes and expenditures to the various levels of government to improve welfare.

In contrast, second generation fiscal federalists adopt a more empathetic narrative. Fundamentally, by disentangling the principal—elected representatives and, ultimately, citizens—from bureaucratic and administrative agents, the basic argument for federalism here is that localizing rewards aligns agents' incentives with the principal. Further, they say, government should not lead economic development, should not be controlling industry. It would do more harm than good if not constrained in its role; instead, those in government should be rewarded for corresponding local private market outcomes. Second generation theorists, like Tiebout before them, still do believe though that amenities and public goods will create a spatial equilibrium: let people move rather than enforcing equality at a lower welfare level. But, they do support at least some proportional revenue sharing to mitigate regional inequality. Still, they argue that the centralized redistributive transfer systems induce greater corruption and rent seeking.

Despite the federalist banter, decentralization has a mixed record on corruption. For instance, Treisman (2000) finds that federal systems are more corrupt than non-federal ones. In defense, SGFF theorists cite their being second generation: subpar setups of decentralization are unlikely to improve welfare. Because competition among subnational governments is one of the mechanisms for policing corruption, decentralization must satisfy the conditions of having a common market and mobile factors of production, give sufficient subnational policy authority to local government, and a hard budget constraint to still regulate local governments. Most decentralized countries fail to satisfy these conditions; therefore, they fail to prevent corruption says the Stanford political scientist, Barry Weingast.

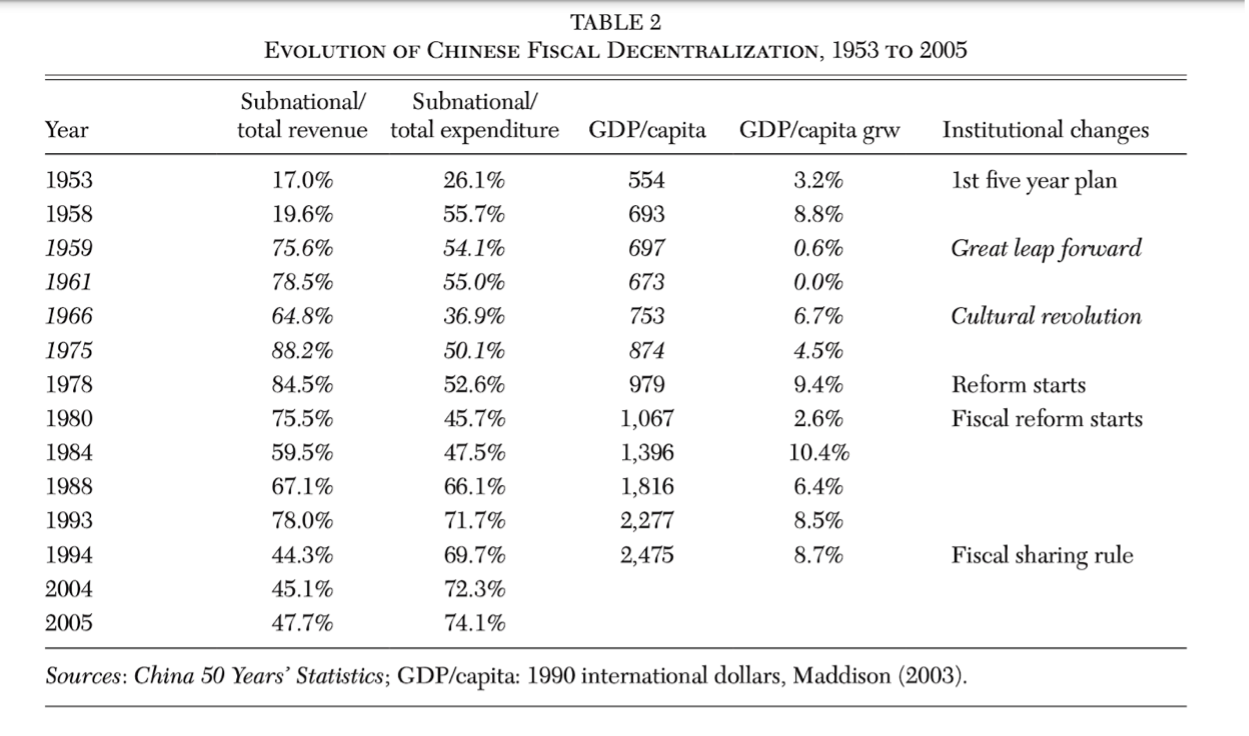

The story of growth in China after the '80s is much debated and a partially open question. There is much competition over the imagination of both what reforms happened and which of these were responsible for the China's rapid growth and poverty alleviation. Jin, Qian, and Weingast (1999) spot three reforms that indicate successful decentralization from roughly 1982 to 1992: local governments got the primary fiscal planning and decision-making role for their jurisdiction, newfound mobility inducing interregional competition, and local incentives stemming from the local retention of marginal revenues.

To elaborate, the Chinese federalist reforms broadly had three themes. First was the decentralization of fiscal regulation, expenditure, and public good provision. Herein, Chinese local governments supervise about three quarters of the state industrial firms in terms of output; they also have a major responsibility for state fixed investments, initially in industry but increasingly in infrastructure. Moreover, local governments have primary authority over regulating local economy, performing tasks like licensing, defining the role of non-state firms, coordinating urban development plans, and even resolving business disputes. Finally, local governments provide an array of local public goods such as schools, health care, culture, police, and infrastructure/facilities. Circularly, such infrastructure plays an important role in attracting foreign investment into their localities. The second theme was around performance appraisal: the promotion of officials who contribute to local economy. The third was China’s new fiscal contracting system which led to large gains in marginal revenue retention for provinces. Five-year contracts were drawn between local government and center on revenue sharing: fixed amounts with annual increments are owed to the centre and the region keeps everything beyond that. Thus, China’s decentralization resembles much of what SGFF theorists would describe as an ideal setup of fiscal federalism.

Typically, research cites three reforms as products of local innovation and competition. First was the institution of the Household Responsibility Scheme of land division and redistribution, moving China from communes to private agriculture. The second was the creation of special economic zones in the Guangdong and Fujian Provinces. The third is the differential profit retention schemes introduced for state enterprises in Sichuan and Hubei which ultimately replaced profit remittances with taxes, beginning the conversion of PSUs to market corporations and beginning the march towards their eventual privatization. Besides these, some also highlight the success of locally managed Township and Village Enterprises, particularly relative to central state enterprises.

Broadly, there are a few theories of China's growth and the role of decentralization in it, often using parallel datasets (say, at different levels of aggregation) and parallel methods to substantiate their assertions. However, across theories, a few things are agreed upon. First, that China viewed decentralized actors as strategic self-interested players, abandoning the premise of benevolence in civil service. It created a positive-sum relationship between government and agents. (Jin, Qian, and Weingast, 1999) The direct implication of this is that performance-based promotions motivated career incentives of bureaucrats to do better. Establishing that performance was being rewarded, Li and Zhou examined the top officials in twenty-eight provinces in 1979-1995 and found promotions were significantly more likely—and demotions less likely—in provinces with higher growth. Similarly, Maskin et al. (2000) found provincial officials were more often promoted to the Party’s Central Committee if their province’s relative growth rate increased. Xu (2011) argues that this tournament style competition in China was an important cause for its growth. Further, there is some agreement that by incorporating regional experimentation into the central government's decision-making process, reforms were less likely to be blocked, and the political and technical risks of reforms were greatly reduced.

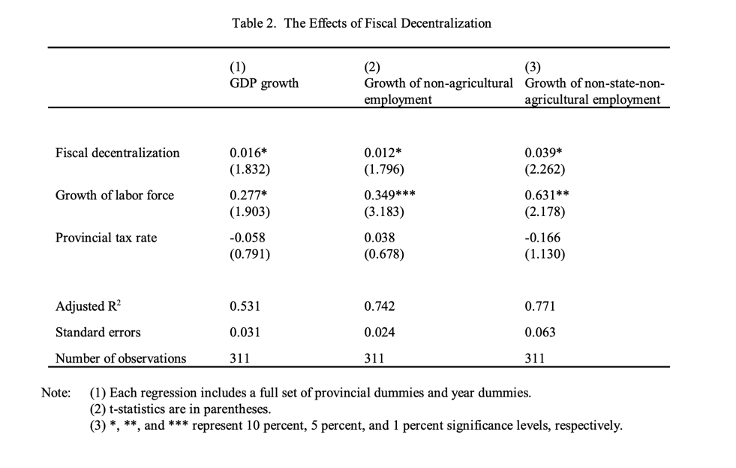

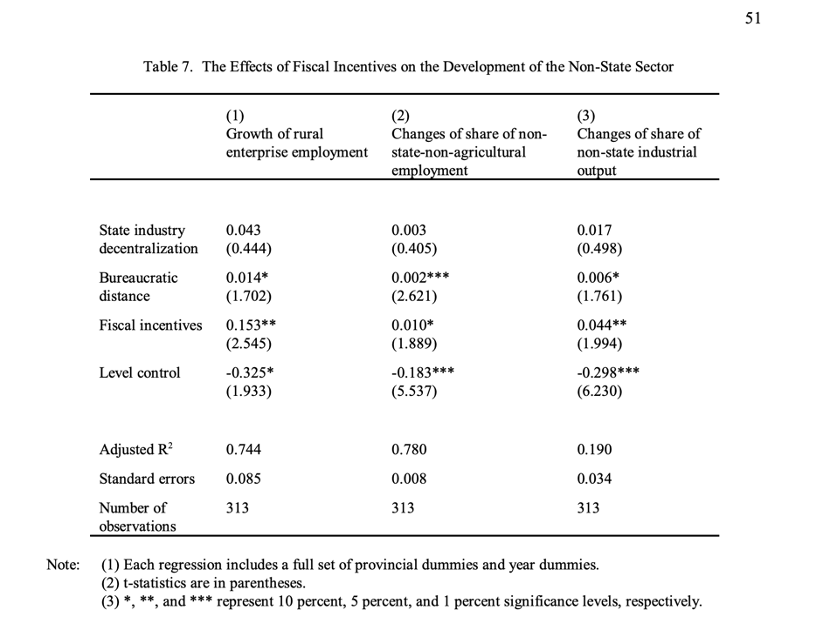

Lacking democracy, the rule of law, and other traditional constitutional constraints on the national government, theorists have long associated China’s transition to markets with the devolution of authority from the central to local governments. They argue that decentralization-induced incentives caused the growth of rural enterprise employment, changes in the share of non-state-agricultural employment, and non-state-industrial output; they also caused improvements in GDP growth, growth of non-agricultural employment, and growth of non-state-non-agricultural employment (tables from Jin et al. below; see Montinola, Qian, and Weingast, 1995; Chang and Wang, 1998; Xu and Zhuang, 1998; Jin, Qian, and Weingast, 1999; Qian, 2002; Xu, 2011). This is in contrast to Andrei Shleifer’s 1997 study of Russia after the collapse of the Soviet Union: despite decentralization, he finds local government revenues were extracted by the aggregating regional government, thereby stealing incentives, and inducing grabbing behavior in Poland and other former Soviet Union territories. So, despite the higher disinvestment of PSUs in Russia vis a vis China during their respective reform years, Shleifer observes lower economic outcomes in Russia, associating it with a lack of decentralized incentives. So, SGFF theories are reverberated in the Chinese evidence, and going even further, Jin et al. (1999) argue that, counterintuitively, this quasi market allocation of resources also improved the horizontal distribution of expenditure across regions.

Qian (2002) also negates some counterarguments to explain Chinese growth as primarily caused by decentralization. Qian argues that the role of FDI was not as significant, and that if it were, West Germany’s relative poverty vis a vis East Germany is hard to explain. Further, he concedes that agriculture liberalization did help, but cannot explain the entire puzzle without including local investments in research and development and on infrastructure.

In contrast, an alternative view of the reform process says that growth-enhancing policies emerged from competition between pro-market and conservative (which in China, funnily means Communist) factions in Beijing: in a bid to win the ideological battle on stateism and communism, Beijing found itself in a policy civil war. This faction says that much of what is called the “local innovation” arising from decentralization was actually CCP top brass heavily and secretly involving local officials to implement their ideas. So, a top-down planning apparatus behind-the-scenes. Cai and Treisman (2006) point to how some common examples of local innovation, like special economic zones, were actually likely centrally-led and how marginal revenues were not actually retained as rewards uniformly as tax rates and revenue sharing rates that were set by the center kept leaving less revenue available for local extraction over time. They also point to the fact that local governments collected a part of revenues even before this reform without any similar corresponding accomplishments vis a vis GDP or growth.

Particularly, while many who are skeptical of decentralization argue that it is unclear if it did or did not do all that much for China, Cai and Treisman go as far as to say that it is unclear if decentralization was even a net positive. They attempt to debunk explanations of fiscal incentives by arguing that these incentives were actually not as strong as presented. Total budget revenues fell from about 28 percent of GDP in 1979 to about 16 percent in 1990, depleted by tax evasion, the decline of the old state enterprises, and difficulties in collecting taxes from the new non-state sector. The actual revenue retained is the product of the marginal retention rate, the tax rate, the revenue sharing rate, and the total revenues. So, in reality, even though marginal retention percentages could have been significant, retained revenues actually fell. So, “incentives” could have actually been weakened through the reform era. Further, they point out that the state enterprises’ budget constraints did not harden despite the theory on incentives. Loss-making enterprises multiplied in the era of decentralization and rapid growth, and the state banks virtually bankrupted themselves bailing them out. Further, they argue that grassroots and provincial efforts may or may not be linked to actual decentralization: as previously described, many of the above big local experiments, especially the SEZs, had a strong central role. Most local leaders were unable to resist central abuse or exertion anyway. Wilson (2016), on the other hand, favours a reverse-causal explanation. He finds a significant and positive effect of economic growth on subsequent quality of governance, largely driven by growth in the secondary sector, but no significant effect of quality of governance on economic growth. So, perhaps it is the market growing that improved regulation and not reforms in regulation that helped the market. But this study makes a provincial comparison which was not the level at which autonomy was given—actual autonomy existed at sub-provincial levels.

Nobel Laureate Ronald Coase, some of whose greatest contributions to economics were perhaps heavily contested by the rise of a heterodox China, has his own theory, writing a book on it with Ning Wang in 2012. Coase and Wang offer a story of Chinese growth that attempts to reconcile the CCP ideological civil war point while still fundamentally demanding federalism. They argue that the traditional Chinese communist state merely survived and endured through federalism and then took credit for what federalism achieved. In that way, they argue that China’s capitalism was not an authoritarian-led capitalism in the true sense. Relevant here is Coase’s own body of work which pushes for securing property rights, eliminating transaction costs, and assuring the rule of law; while China was originally imagined as a counter-argument to Coase, Coase posits that it was the increasing creation of (less and less quasi) property rights and the formation of more agreements and contracts under unpropitious legal circumstances that led China to glory.

So, in Coase's version, while Beijing and the Politburo certainly had some role in China’s growth, it was markets that were the turning point. He credits Beijing only for revitalizing PSUs, for Hua Guofeng’s Leap Outward—a state-led, investment-driven program with a focus on heavy industry, and for Deng Xiaoping’s and Chen Yun’s macroeconomic adjustment—movement from heavy industry to consumer goods and agriculture, decentralized foreign trade—and microeconomic reforms—state-enterprise reform to offer greater autonomy and profit retention. Whereas, Coase argues, the creation of SEZs, the shift to private farming from communal agricultural, the growth of private capital and business, the advent of local Township and Village Enterprises that went on to outperform central PSUs, and the competition-induced speed of governance were all babies of decentralization.

Qian (2002) argues that the solution for China came from transitional institutions that allowed growth despite the lack of rule of law and secure private property rights, contrary to popular wisdom on institutions (like that of Coase). China improved economic efficiency by unleashing the standard forces of incentives and competition while also making the reform a win-win and, thus, interest-compatible for those in power. This is sort of a “second-best argument” which states that removing one distortion may be counterproductive in the presence of another (harder to remove) distortion. So, compromising with the CCP and finding second-best reforms, China exploited transitional institutions to manage its economy while satisfying its political economy.

Qian presents five examples of such transitional reform. These are listed as follows. (1) The Dual Track system: under the plan track, economic agents are assigned rights to and obligations for fixed quantities of goods at fixed plan prices. At the same time, a market track is introduced under which economic agents participate in the market at free market prices, for all marginal goods above the fixed quantity in the plan track, thereby allowing the market to work; (2) Township Village Enterprises’ unique ownership structure that created incentives in revenue growth for both the centre and local government; (3) fiscal contracting which ensured fixed revenue sharing with planned increments while still allowing marginal revenue retention; (4) anonymous banking (another second-best approach); (5) SOE reform (rather than privatization or disinvestment). Cheung (2014) agrees with Qian on the importance of transitional institutions. In simple terms, Cheung says, even if property rights were not secured and ownership was weak, use rights were secured for the utilization of the asset. These examples demonstrate how a transitional state deals with its sticky, authoritarian political establishment while slyly embracing the market.

This is all, of course, only the debate within neoclassical economics where the debate flails around the question of what aided the capitalist shift in China but not over whether the capitalist shift was responsible for growth. For instance, Tang et al. (2018) use a natural language processing method to confirm that there has been a rise in the frequency of neoliberal language in laws and regulations up to 2000, but argue that provinces’ market reforms do not seem to contribute all that much to their GDP per capita and foreign investment growth. Specifically, they point out that, year and province fixed effects—effects caused by attributes and qualities of the place or the year—can already explain over 70 percent of the R-squared of provincial growth regressions.

Weingast (2008) dictates how India should find market-preserving fiscal federalism. Market preserving federalism satisfies five conditions:

In contrast, despite partial federalism, Weingast points out that the Indian government's regime has failed in the following ways (especially through the 1990s):

The Finance Commission's transfers of revenue to states in India reflected a series of weights for different criteria: 62.5 percent is negatively related to a state's income, so that poorer states receive greater funds; 10 percent on the basis of population; the remainder relies on state size, infrastructure, tax effort, and fiscal discipline. This means that most of an increase in local revenues goes to the centre. Thus, many of the best-performing states then enter an arrangement where they pay more taxes than they receive revenues and where further improvements might grow this deficit—hurting incentives. So, centralized federalism prevented Indian provinces from innovating and fostering more market-enhancing local economies. Importantly, Weingast argues that as the center has loosened the constraints on states, states have become more innovative, and India’s economic growth has improved significantly.

However, a nuanced transfer system could work towards achieving all three ideal goals of revenue sharing—horizontal equalization, preventing price competition by lowering taxes between states, and ensuring high marginal fiscal incentives—by designing transfer systems with non-linear functions. This means that the poorest provinces with only limited capacity to grow in GDP or to increase taxes should be treated in a manner similar to their current treatment: great care and investment. For other provinces, Weingast proposes that the center keeps track of revenue collection by province and uses a step function to capture a moderate or moderately high proportion of revenue generated from a province up to a revenue level fixed in advance and then allows the province to keep a high or very high proportion of all revenue raised above that level. This still preserves high marginal incentives to foster local economic prosperity.

While there is much to change in the management of India's public finances, China's experiences raise more philosophical questions as to whether there is need for reorganization. Of course, particularly on the tax collection end, federalism has made things difficult for China and this must be kept in mind as well. Cui (2014) laments that a more rule-based regime with less weight and discretion for local officials would have made tax collection far less leaky. Similarly, evaluating the current state of affairs, Ahmad (2011) raises concerns over signs of fiscal indiscipline in some states as borrowings increase and hopes to tighten the gap between local government revenues and expenditures.

I will leave this discussion here and allow you to proceed to read my older post on fiscal federalism for India and the particular context of India—GST and who should borrow.

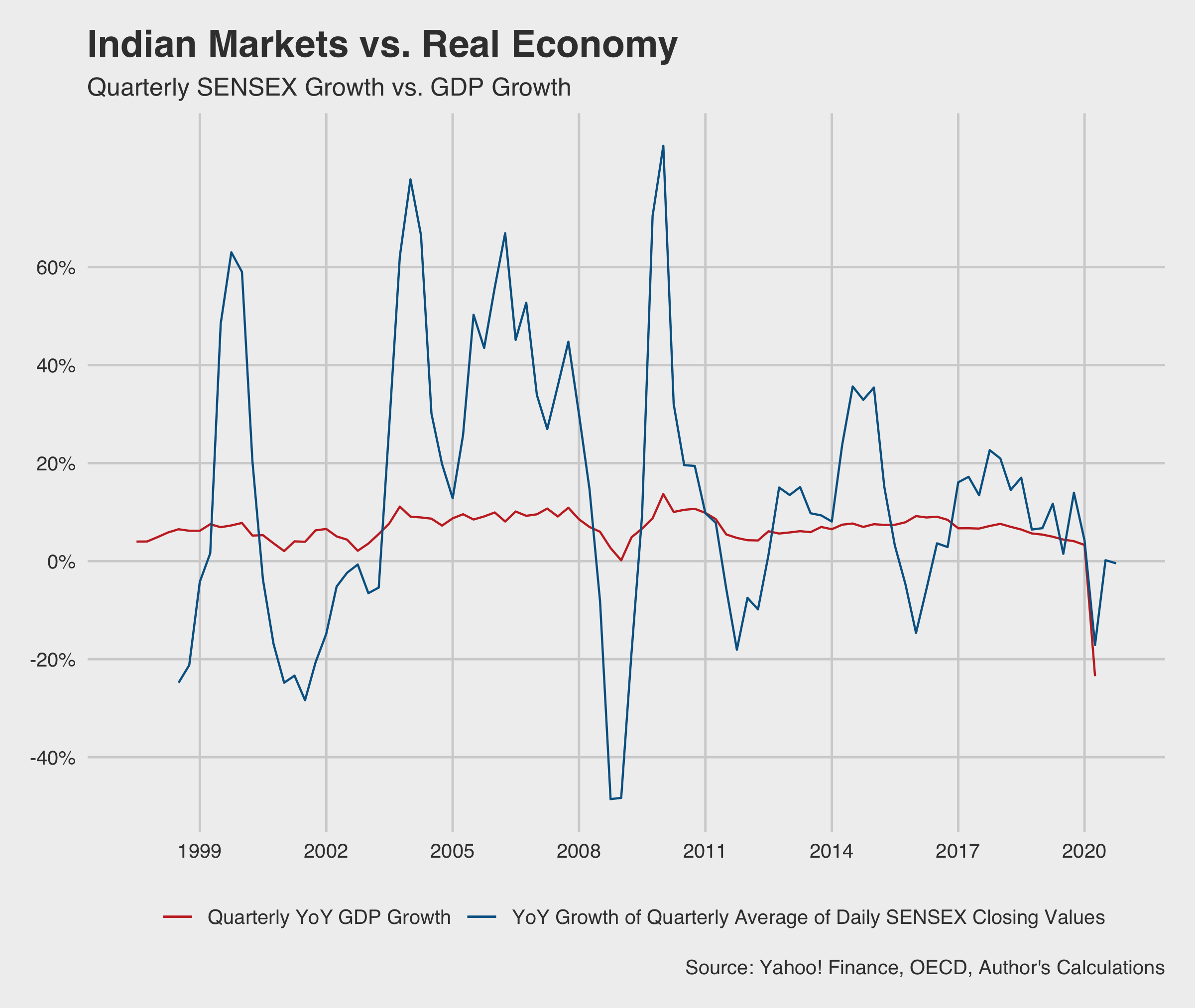

Yesterday (on the 15th of October), as many predicted, the market crashed with the SENSEX falling by over 1,000 points, all sectoral indices were in the red, and equity investors lost Rs 3.3 lakh crore (INR 3.3 trillion). With rising unemployment, destroyed or subdued demand, poor fiscal stimulus announcement after announcement, loan restructuring, and the previous aggressive bullishness in the market, both a general decline and this particular crash seem warranted. However, today, on the 16th, the SENSEX is up by around 250 points, seemingly recovering ~25% of the wealth lost yesterday. This volatile bounce back triggered me to write on the growing, increasingly erratic gap between our stock markets and real economy. I wanted to attempt to describe the difference between Dalal Street and Delhi’s North Block, to myself and here.

To put it differently, this is the kind of data journalism I'd like to see a lot, that I don't really see; the main intention of this post is to share this graph (the two lines have a correlation of 0.506 and the two rates have a t-value of 5.45 with a p-value < 0.001):

I do not think we understand this gap or its wideness perfectly yet, both at home and globally. But a few perspectives seem sensible.

First, I think there is a market perception of a definite recovery. For one, there is the idea that given that everything has already crashed, things can only move upwards. Further, it seems to me, there is an expectation (almost an implicit reliance) on the idea that fiscal stimulus and government intervention will and must happen (it has happened globally, to some extent). This seems to be keeping market appetites up as, if things will only go up hereon, long positions seem more warranted. There is some value to this line of throught: Deutsche Bank estimates total fiscal and monetary stimulus at more than US$ 10 trillion in the G7 countries alone which will make it five times more than the stimulus the G7 rolled out after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. While central banks have tried to ensure that the market doesn’t crash to a severe extent, it seems like their actions carry disproportionate weight in market enthusiasm. So much so that the RBI had to intervene to rationalize yields on state bonds recently. As the Economist writes this month, “This rosy view from Wall Street should make you uneasy.”

But second, as many experts point out, it seems like the markets are growing increasingly detached from real world outcomes, betting purely on future profits. Business fundamentals seem to remain poor and lost demand is yet to revive, but the market doesn’t seem to care. As JP Morgan notes, “The S&P 500 is only 15% below its all-time high, reached on February 19, 2020, and it trades with a forward price-to-earnings multiple that is the highest since the dot-com bubble in 2000.”

The Economist does a good job of pointing out why this is all dangerous, pointing to the devastation a second crash could now cause if/when nations enter second waves of infections and if cost-cutting doesn’t save the GDP after all, incentivizing fraud as hiding your losses is more important when the market is recovering aggressively (whose eventual revelation would also shock the economy), and the anti-corporate political backlash that could ensue if big corporations continue to grow while smaller ones struggle. All of this mean that the “things can only get better” narrative is dangerous and might itself cause crashes in the coming days.

The RBI just announced (three hours ago today, the 9th of October) that it is conducting open market operations on state government bonds. That is, the RBI is going to be buying loans of states. This is the first time in history that this move is being made.

(A bond is an instrument of debt. When you buy it, you give the government money which will be returned to the owner of the instrument at a later date with interest. That is, you buy debt.)

This move is very interesting especially in the context of the debate on who should borrow (particularly to make up GST shortfalls). So far, states say that the center should borrow and give to the states because it gets a better interest rate. Meanwhile, the center says its deficit is too high (or that it wants to preserve the room for deficits to increase) and, so, states should do it.

Simultaneously, in the non-COVID recent past, there has been an effort to create differentiated rates for different states. The rationale for this being: why should, say, Maharashtra or Tamil Nadu pay the same rate on debt as Uttar Pradesh despite distinctly better fiscal performance. Any reading of this debate immediately brings parallels to the European Central Bank and how Greece/the PIIGS nations launched into a sovereign debt crisis (i.e., couldn’t pay back their debt) due to severe fiscal indiscipline (spending too much to win elections) because they were enjoying the low rates enabled by the implicit debt guarantee on their borrowings (given contagion—aka crisis spreading—risk for the Euro area) from the European Central Bank and, therefore, France-Germany.

Now, in the post-COVID era, especially with the GST shortfall, the question is should we prioritize a very federalist fairness, set efficient market rates, and reward and enable good governance or should we (indirectly) subsidize debt for poorer states?

This is all perhaps why RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das said today, “This is important from the point of view of smooth and seamless transmission of monetary policy impulses as well as the completion of market borrowing programmes of the centre and states in a non-disruptive manner with a normal evolution of the yield curve.”

As is, even discounting the public health costs and the need for much larger expenditure to revive our economy after the virus, states’ capital expenditure—spending on infrastructure or projects—has been steadily declining due to lower funds. With restrictions on borrowing, states have been spending mostly on revenue expenditure—i.e., mostly paying salaries for existing work. This likely means there’s a significantly lower than desirable multiplier on state expenditure. In other words, every rupee spent by the government is someone’s income, who then spends it to create someone else’s income, and so on ad infinitum. So, when an external party, i.e., the state adds new consumption, it has a “multiplier” effect on everyone. Typically, when you spend on infrastructure, you create a far better multiplier effect besides the direct economic benefits of having new roads or, say, more electricity.

Now, for the first time ever, RBI is buying the debt of states. This will be bought in the secondary market at a market-linked price—where existing owners of bonds sell them to buyers. So, as states issue more bonds, more people will buy them because the RBI is buying them from you.

A usual auction of bonds has a “spread.” The spread is the additional money that the investor seeks on top of the bond’s value to buy it—it is how the market sets the prices of bonds. So, right now, with states increasing borrowings after COVID-19, spreads are naturally higher—the more indebted you are, your additional new debt becomes less attractive. So, if spreads remain high, either fewer people invest in state governments or they do so with a less attractive deal for states. The RBI doing this will reduce the spreads on bonds by making them a more investable asset. So, this will allow states do more auctions and get more funds. As per the RBI calendar, states are expected to borrow an additional Rs 2 lakh crore during the October to December quarter.

This will also rationalize and cool down the yields on SDLs (as state bonds are called—state development loans) which have been a bit crazy in comparison to central government bonds (G-Secs or government securities). “SDLs are going through the roof at about 100 basis points (bps) right now, and hopefully that will come down,” said Neeraj Gambhir, the CEO of Axis Bank, to CNBC-TV18.

How much of which bonds/states at what prices will the RBI end up buying? What will be the effect of this on the pricing of state government bonds? How lower will spreads get now that the RBI is showing confidence in state debt and demanding it more?

The 2020 Budget allots around 3% of our GDP to education; independent of whether this allocation suffices, in real terms, this is a hard number to visualize: a whopping Rs. 99,300 crores (13.56 billion USD)—of which schools get 59,845 crores. Meanwhile, in 2016, we spent 80% of our education budget on teachers’ salaries. That means that most of our monies get spent on revenue expenditure—funding the schools that exist. That also means that a 1% increase in efficiency—that is, if for the same inputs, achieving 1% better outcomes—saves ~599 crores. And because money saved is money created, making sure that we get the maximal bang for the buck on spending has been a focus of public finance. When we contextualize this in education delivery, a potentially powerful tool to achieve more with less is school inspections.

Education being a concurrent subject in India, while the center regulates education, the frontline delivery of service largely rests upon states. Ultimately, with many types of schools run by different sources, this results in significant diversity in the model of inspecting schools. Generally, however, inspections come into the jurisdiction of the District Education Officer and the Assistant Educational Officers (their names vary by state); the system usually has one mandated annual inspection, likely one mandated surprise visit, and encourages as many regular surprise visits as possible. The focus of visits is typically primarily on evaluating the infrastructure and sanitation of the school although they usually also mandate some examination of students’ academic levels and teacher instruction and pedagogy.

Largely speaking, to an outsider like me, it appears like our school inspection system is broken. How do we do good better?

An important principle in political economy is to design policy by viewing the different actors as strategic players maximizing their self-interest in a game—this is an important approach as the difference between imagined policy ex ante and implemented policy ex post often comes from the incentives of those implementing policy diverging from the “ideal” incentives. This is a lesson for reformers to design policy with the sophisticated expectation that frontline actors are acting in self-interest (not to ignore that for many, self interest might rest entirely or partially upon doing good).

Further, the usual (and a very sensible) formulation of this incentive mismatch is in the form of a principal-agent problem. The principal—the citizenry—entrusts the political executive and top bureaucrats—the first level agent—who then entrust the frontline official—the ultimate agent—with service delivery. The underlying issue with this delegation is that the principal cannot observe the work of the agent, they merely observe the outcomes of the actions. That is, the work that needs to be done is un-observable. A particular confound in the context of government and, particularly, our government with its poor administrative data and lack of evaluation of public services is that not even outcomes are observable, only monetary inputs are. So, while a restaurant owner can at least observe her manager’s sales if not the manager’s customer service, the citizenry doesn’t have high quality information on the outcomes of, say, education efforts. However, the budgetary inputs are announced and observable. This results in a paradoxical state where the outcome is the input—we laud policies that spend more because that is all that is observable to us. Ultimately, neither do we have control on the bureaucrat’s effort nor do we know whether this bore fruits in terms of, say, foundational literacy and numeracy levels, dropout rates, or reading levels.

In this context, the inspection of schools induces observability into the system; it actually tells us how well government schools are using their limited resources and also how well private schools are run. But, all this, only if the inspection works…

I’ve first hand seen teachers transform into pedagogy gods when inspectors watch—new teaching aids appear, digital tools are used, and a previously empty blackboard is quickly filled up by interactive exercises. Imagine if teachers had seven days notice to the important annual inspection? That would hardly measure a “routine working day”, right? Well, don’t imagine, this is the system in, for instance, Kerala.

A worse outcome would be corruption: if you knew who your inspector was and when they will show up at your gates, as a headmaster, you are well equipped to bribe your way into a good report.

Three things can be done to structurally restrict the ability to bribe your inspector. First, for the mandated annual inspection that has the power to issue warnings, recommendations, or take more serious action, standardize panel inspections (like Delhi does) where a panel of the inspector and randomly selected local headmasters and principals inspect schools. Where it is geographically viable, select these headmasters and principals from other zones in the district that the AEO (the inspector for each zone) does not oversee. Second, introduce day-of intimation for annual inspections—this only serves the purpose of ensuring that that day is a routine working day for the inspected school. Third, for non-mandated surprise visits, randomly assign inspectors to schools. The goal-setting system (reform #3) allows inspectors to commit to visits and use a management information system to see who they’re visiting in the commited visit just before they leave their office. Further, once we introduce accuracy scores for inspectors (as proposed in reform #4) and have quantitative measures of school performance (from reform #2), we can do much more with this random assignment like assigning visits to poor-performing schools more frequently and assigning high trust score inspectors to low score schools.

Side note: there might be value in inspector discretion, but many systems like that in Delhi already have higher level bureaucrats assigning inspectors to the mandated inspection on the day of inspections.

Measurement has three issues right now: first, it focuses on infrastructure over academics (I speculate, a part of the hangover of stage 1 of independent India’s education effort—ensuring access before being able to think of quality); second, it is entirely qualitative and subjective to the frontline inspector enabling corruption; and third, the report once submitted and shared with the school is allowed to collect dust without use (for many states, the only information available pre-visit seems to be last date of inspection and the corresponding inspector).

It follows then that the measurement system must do three things: first, increase focus on examination of students’ levels and teachers’ instruction; second, create clear quantitative scores for different categories like student levels, instruction, teacher and student attendance, dropout rates, infrastructure, sanitation, etc. and compute an index summarizing school scores (Kendriya Vidyalayas do something similar); and, third, explicitly measure improvement in these categories vis a vis past years.

This set of reforms ensure that what is being measured is indeed what matters for students and ensures that inspectors enter inspections with rich records of past inspections. These inform what they should spend time examining and allows them to see and reward improvement. To further enhance this, inspectors could be given readymade tests that include, say, scientifically approved reading level tests to use and be given a MIS with searchable, high quality data from past reports.

The state delegates its duty of care over minor citizens to parents precisely because (in the majority of instances) parents are actors who care about their children and are (at least relatively) well informed about their children’s lives. Soliciting parental feedback and complaints is an easy way to build state capacity without doing much. Allow the end-user to supplement reports with their high quality information on their experiences with the real routine working day.

Kremer et al. (2005) find that 25% of Indian public school teachers are absent on any given day and less than half of them actually teach even if they attend class. Remember, 80% of our budget goes to paying teachers. Presumably then, surprise visits are an important check on teacher absenteeism. Unfortunately, not in the real world. There are many anecdotal accounts on record of teachers and administrators that testify that surprise visits are a joke—they are reported at the whim of the inspector and very rarely does a visit that occurred on paper actually occur.

If we are to exploit surprise visits, we must first make each officer set goals for the number of visits they will complete in a year ex ante. This way, we can include their visits in their performance appraisals (re: reform #5). But, we also need to ensure that the visit actually occurs—perhaps here we should exploit technology by creating tablets or apps that lodge surprise visits and ensure same-day report submission. This tech tool could require photographs of the visit and could record the geo-coordinates of the inspector from the time of the visit till the time that it ends. As discussed, a more powerful solution would allow inspectors to commit to a visit at a certain date-time and then only tell them who is being visited just before. An even more powerful one would randomly assign inspectors to schools because knowing your inspector enables corruption and assign high score inspectors to poorer-performing schools.

While inspectors can help mitigate the principal-agent problem in education delivery, ironically, inspectors are also agents who induce the same principal-agent problem. So, appraising their performance, tracking their efforts as much as possible, and rewarding better inspectors, say, via pay and promotions, is important. This furthers rewarding good, honest work and reduces the relative seductiveness of corruption. Appraisal could also track the zone that the inspector operates in and reward them for actual outcome improvements. Further, backchecks (where a smaller subsample of the total sample are re-tested to determine the accuracy of the first test) could be used to generate scores of accuracy of inspectors.

Quantitative measurement does not mean that teachers’ creativity and freedom should be shackled. Moreover, an explicit purpose of visits is to give teachers feedback on their pedagogy. So, job aids should be created for inspectors to be able to give better feedback for teachers. Multi-day visits that focus on visiting each teacher’s class and giving them detailed feedback should be encouraged and rewarded in the performance appraisal system. Many states already require somewhat regular meetings between education officers and local headmasters and principals: these should also be tracked and enforced as in reform #4, and inspectors should be given pedagogy materials and external support as viable to do more with these meetings.

To defeat the principal-agent problem in education delivery, inspections could be exploited. However, to defeat the principal-agent problem in education inspections, we need to introduce new extrinsic incentives like pay and promotion based on actual performance, restrict the possibilities of corruption and collision by reducing notice time, randomizing inspectors, and tracking the trust levels of inspectors, and improve measurement by talking to parents, changing what and how we measure, and using measurement to do more. Some of these require robust technological tools.

Ultimately, as we improve our data on schools and understand which schools work, we can then figure out why. That way, we evaluate policies, compare them with others, and constantly strive to do more with the same resources. The data is also an end by itself—some computed indexes on school scores could be released publicly to inform parents for school choice. The stakes are large here.

*This post is inspired by the thinking of Dr. Santhosh Mathew, Country Lead of Public Policy and Finance at Gates Foundation India, whose state capacity approach I have been working on under him.

Notes from a guest lecture I delivered in March 2019 at the Department of Computer Science at Stella Maris College, Chennai, offering a simple introduction to GitHub with R and R Markdown.

But what is version control?

- Simple analogy: Google Drive for developers

- Track and manage changes to your code

- Version control lets developers safely work through branching and merging

- Work with online Git repository

- Make changes in your own branch

- Merge with online cloud branch

- Changes are tracked and can be reverted if neededMake your account and install into RStudio

install.packages("devtools")

- If this doesn't work, you might need to update your R

- Update at https://www.r-project.org/Start your first project

Quick note

*.Rproj in your .gitignore)readme.mdMore information: https://www.datacamp.com/community/tutorials/git-setup

Very simple guide on the workflow: http://rogerdudler.github.io/git-guide/

A more detailed guide: https://happygitwithr.com/rstudio-git-github.html

Use man git in Shell for help

git commit -m "Commit message"git push origin mastergit pull“R Markdown is a file format for making dynamic documents with R. An R Markdown document is written in markdown (an easy-to-write plain text format) and contains chunks of embedded R code, like the document below.” - https://rmarkdown.rstudio.com/articles_intro.html

Very simple. Next time you make a new file, make it a R Markdown file instead of a R script and save it as x.Rmd

Chunks

A mini-R-script in the middle of your text, headings, etc. in Markdown

E.g.:

library(tidyverse)

# Making a random dummy dataframe

x <- data.frame(replicate(5,sample(0:1,1000,rep=TRUE)))

# Print three rows of our dummy df

x[1:3,]

## X1 X2 X3 X4 X5

## 1 1 0 0 0 0

## 2 1 1 0 1 0

## 3 0 1 1 1 0

Chunk Options

You might not want to show your code, the warnings, and messages but show the output—Rmd let's you control that.

E.g.: There's a hidden chunk below but you'll only see the table it outputs:

| Cool table |

|---|

| X1 |

| 0 |

| 1 |

Global Options

You can also initialize a setup chunk with global chunk options like below.

knitr::opts_chunk$set(include = TRUE, warning = FALSE) # Random chunk options

Here's a cheat sheet!

Cmd or Ctrl + Shift + K to knit to chosen formatAlternately, edit the YAML header at the top of the file. Options include:

output:

pdf_document: default

word_document: default

html_document: default